This blog seeks to delve into the fascinating world of the Ad Nauseam extension – a tiny app that caused worldwide panic throughout the PPC industry.

As well as looking at examining the furor caused by the Ad Nauseam extension, we’ll show you how this browser extension could still be a threat to your Google Display Ads, as we break down the financial implications of Ad Nauseam for individual industries like education, e-commerce, and travel and tourism.

What is the Ad Nauseam Extension?

Obfuscation – “the deliberate addition of ambiguous, confusing, or misleading information to interfere with surveillance and data collection.”

This digital definition, provided by Finn Brunton and Helen Nissenbaum in their 2015 manifesto, ‘Obfuscation: A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protest’, provides a modern context for an ancient tactic of combat.

Obfuscation has been used for centuries in war and espionage to conceal the vital amongst the irrelevant. In their book, Brunton and Nissenbaum provide the perfect example from World War II, when fighter pilots flying over enemy territory would release chaff – pieces of black paper covered in tinfoil, cut to match the wavelength of the radar systems used to detect them.

They knew they couldn’t hide. So they released a perfect storm of irrelevant distractions.

This was the time-tested principle Nissenbaum drew on in 2014 when, together with Daniel Howe, she created the Ad Nauseam extension, built on the same principles as their earlier creation, TrackMeNot. They were looking to combat the unnecessary invasions of privacy internet users are subjected to every day by search engines and advertising networks.

TrackMeNot intentionally confuses search engines by periodically making search queries about random subjects on the user’s behalf. This creates a random profile of interests that obfuscates the user’s real interests and intentions – so any information the search engine holds about that user is of no use whatsoever to advertisers.

The Ad Nauseam extension was also designed to obfuscate the user’s real intentions and pollute data used by advertising networks. But there’s one important difference – Ad Nauseam doesn’t just let users evade advertisers.

It lets them bite back.

How does Ad Nauseam work?

Installing the Ad Nauseam extension results in an ad-free browsing experience for the user, much like any of the standard ‘ad-blocker’ tools such as AdBlock Plus or Privacy Badger.

However, every time Ad Nauseam ‘sees’ an ad, it blocks it AND clicks it – applying a financial penalty to the advertiser and polluting any data associated with the click, ruining any retargeting marketing strategy.

It’s indiscriminate, and if the user is a regular visitor to pages where your adverts are often placed – for example, if they’re a tennis fan, and you sell tennis merchandise – then it can potentially put a regular hole in your budget.

This wasn’t just a general anti-capitalist sting operation, as Nissenbaum and Howe were careful to point out:

“…it is not, as we make clear on the project page, advertising that is the primary target of the project, but rather the tracking of users without their consent.

“Toward this end, we have enabled support in AdNauseam for the EFF’s DNT mechanism, a machine-verifiable, and potentially legally-binding, assertion on the part of sites that commit to privacy.”

Any publisher that committed to the ‘Do Not Track’ function advocated by the Electronic Frontier Foundation was safe from the clicks of the Ad Nauseam extension (this feature was added later, after some consideration).

‘Do Not Track’ functionality provided users with a simple tracking opt-out at the browser level. Unfortunately, DNT withered on the vine due to low levels of adoption. It’s been argued that the demise of the DNT initiative was a great loss, and indirectly responsible for subsequent privacy developments such as GDPR and the planned abandonment of third-party cookies.

Nissenbaum and Howe published an academic paper that outlined the purpose, methodology, and results of their work with the Ad Nauseam extension, in response to Google’s removal of both Ad Nauseam and TrackMeNot from the Google Chrome Store.

Why did Google remove the Ad Nauseam Extension from Chrome?

In retrospect, Google’s zero-tolerance response to this blatant assault on their primary revenue stream wasn’t a shock. It’s more surprising that the app was allowed to remain on the platform for three years.

Google pulled the Ad Nauseam extension from the Chrome Store without warning in January 2017. When Daniel Howe contacted Google for an explanation, it responded only that Ad Nauseam violated a clause of the Store’s Terms of Service, stating “an extension should have a single purpose that is clear to users.”

When pressed further, Google added that an extension should not be ‘both blocking and hiding’ ads. It refused to respond to any further questions from then on.

This disingenuous explanation does little to disguise the fact that Google was clearly no longer willing to accept an app that targeted advertisers – its main customers – with deliberate invalid traffic and malicious clicks.

The extension is still available for download – but if you want to use it with Chrome, you’ll have to manually install it, which is a fairly tricky and time-consuming procedure.

The Ad Nauseam Dilemma: Between Privacy and Click Fraud

More than 78% of US internet users surveyed in 2018 responded with a negative statement when asked to choose a description of their feelings about digital ads. The most popular response chosen, with 41.7% of the votes, stated that ads were ‘too aggressive in following me on every device or browser’.

And Americans are even less enthused about the way their private data is gathered and processed by companies. 79% say they’re concerned about the way their data is used, 81% feel that the risks of such data collection outweigh the benefits – and 59% don’t understand what these companies are even doing with the data.

But does this justify financially battering businesses? Companies that are just trying to get by, with payrolls to fill and families to feed – companies that may well serve their communities in any number of valuable ways? If an advertising network offers you a competitive edge (albeit one based on internet user data), then it’s difficult to ignore that.

At the end of the day, even though their motivation is moral rather than financial, isn’t the Ad Nauseam extension just…click fraud?

A private citizen’s dream, an advertiser’s nightmare

Nissenbaum and Howe disagree. They point out ‘fraud’ indicates financial gain for the offender, and that “in litigated cases of click fraud, the intention to inflate earnings has been critical” to the judicial decision to convict.”

In their paper they argue that in the absence of a financial incentive, advertisers have no right to expect internet users to cooperate;

“In some of the most revealing exchanges we have had with critics, we note a palpable sense of indignation, one that appears to stem from the belief that human users have an obligation to remain legible to their systems, a duty to remain trackable.

“We see things differently; advertisers and service providers are not by default entitled to the externalities of our online activity.”

Will the death of third-party cookies provide better privacy?

While Google’s declared intention to phase out third-party cookies in 2024 may at first seem like a step in the right direction, there are many in the industry who fear that Google’s motivation isn’t to protect user privacy.

While the cookie phase-out means that publishers and advertisers will no longer be able to directly access data about their online visitors, they’ll still be able to continue retargeting users based on information about their search history and preferences.

The major difference is that Google will hold all the cards, and all targeting of ads will either be conducted using ‘black box’ ad algorithms like Smart Shopping or Performance Max, or by massive corporations who can afford to invest in their own first-party cookie solutions like server-side tagging.

Whether this provides better data protection for internet users or not will depend almost entirely on what data Google chooses to collect and monetize.

Alternatives to the Ad Nauseam extension

While Ad Nauseam can still be downloaded and installed via a messy process, there are plenty of other options to rid your internet browser of unwelcome ads (though none that offer that uniquely combative ‘invalid click’ functionality).

Ad blockers and privacy plugins like Privacy Badger and Ghostery will provide you with an ad-free, untrackable browsing experience. Other plugins offer a fun alternative – add-art keeps the positioning and dimensions of on-page ads, but replaces them with artwork drawn from a repository of images.

How much money are advertisers losing to Ad Nauseam?

We wanted to see how much damage Ad Nauseam might be causing to different industries we work with regularly, so we’ve put together some data for you. Disclaimer – while we’ve done our utmost to provide you with the most accurate data possible, there are several (very) broad assumptions and generalizations underlying our calculations. We’ll point these out as we go.

How we’ve calculated our estimates

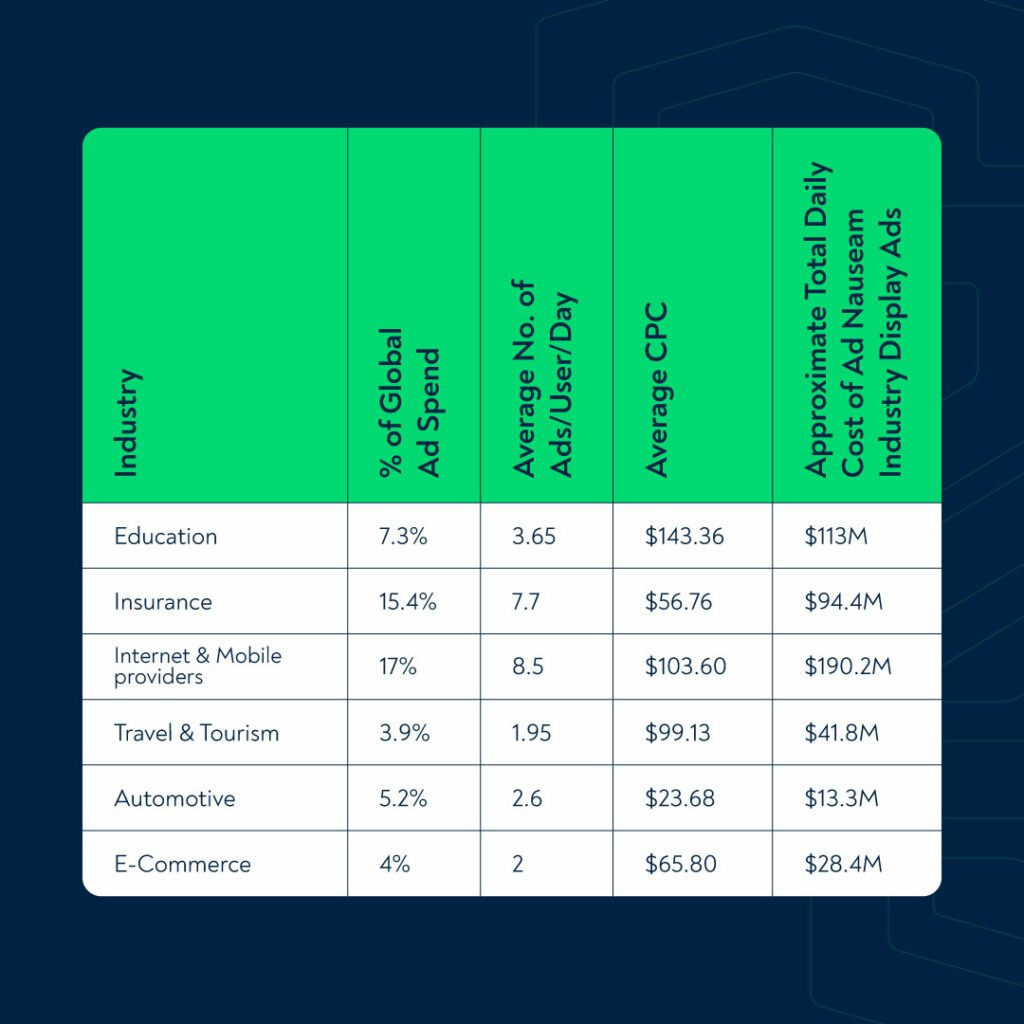

For our purposes, let’s assume that our 216,000 users of Ad Nauseam are an average bunch.

Their browser is subjected to an average of 200 display ads a day (based on the reported number of ads blocked daily by a popular ad blocker)

Their interests vary, but because they’re untrackable with no preferences profile, the ads they’re shown are probably dominated by the industries that spend the most on digital ads (we’ve used the stats from 2021 here).

The lack of personalized data also means they’re unlikely to be targeted by ads that are aimed at affinity audiences or demographic groups. From the four main targeting options provided by Google Display Network, the only option likely to be shown to an anonymous Ad Nauseam extension user would be ads targeted by the In-Market segment, as these are placed in the context of the topic of the web page visited or search terms used.

Usage of each of the four targeting options varies between industries – as a rule of thumb, we’ll take it as read that In-market segment targeted Display Ads represent 25% of the total spend.

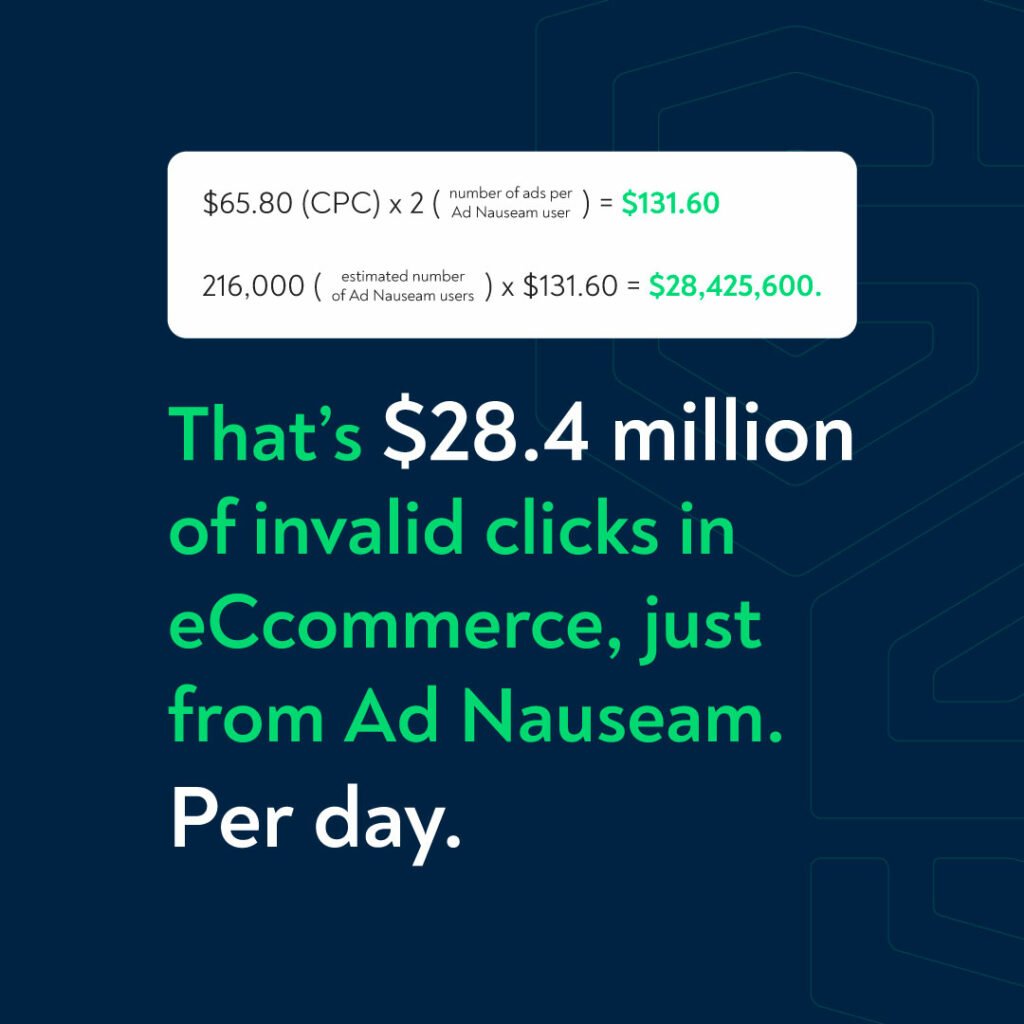

So if we know that e-commerce accounts for 4% of all digital ad spend, it stands to reason that each user would encounter – and click – around 2 e-commerce Display ads per day, through their Ad Nauseam extension.

The average cost-per-click for eCommerce Display Ads is $65.80 (CPC stats here). So,

$65.80 (CPC) x 2 (number of ads per Ad Nauseam user) = $131.60

216,000 (estimated number of Ad Nauseam users) x $131.60 = $28,425,600.

That’s $28.4 million of invalid clicks in eCommerce, just from Ad Nauseam.

Per day.

It’s a staggering figure. And if you’re an e-commerce PPC advertiser, it’s fairly terrifying.

Here’s how it breaks down for six of the industries that are most dependent on PPC.

In practice, even as a rough estimate, these numbers are extraordinarily high. It’s more likely that the lack of personal data means that the pain of Ad Nauseam is spread across a wider set of industries, and that in-market segments are a much less popular targeting option than we’ve given them credit for.

However, as Google moves towards ‘black box’ advertising systems like Performance Max, and advertisers lose control over their targeting options, there’s no telling how much of your budget will become vulnerable to risks like the Ad Nauseam extension.

Click Fraud Protection – a perfect tool in an imperfect world

Here at ClickGUARD, we’re totally sympathetic to anyone with online privacy concerns. Our entire business is intended to protect our customers from the misuse and abuse of their digital assets. And just like Nissenbaum and Howe, we live in hope that one day our digital advertising ecosystem will be replaced by a “transparent, trust-based accommodation of respective interests.”

But until the tech giants who hold us all in the palm of their hand face up to their responsibilities, our role will be to protect hard-working online businesses from click fraud and invalid traffic – regardless of the motives of the operator behind it.